Venturing into Large Format (Part 1)

After having spent so much time with 35mm film and so-called full-frame (digital) sensors, I finally start taking first steps into the land of large format photography. The idea for this experiment arose pretty early, long time before I started with digital – even before I tried my first 35mm slide film. I am not sure what really kept me from giving it an earlier try – maybe it was the rather poor results from my home-made pinhole camera, maybe I was just scared things might get too complicated, maybe I was just too lazy or maybe even a lack of budget? Probably a bit of everything I just mentioned.

So what are actually the reasons for giving large format photography a try? For me personally, the answer consists of several aspects:

So what are actually the reasons for giving large format photography a try? For me personally, the answer consists of several aspects:

- Large format to me always appeared like a journey back in time, back to the roots of photography.

- While larger and maybe a bit more complicated to handle, large format cameras often are rather simple in their design, with a lack of electronics, batteries and fancy features: just a lens, a shutter, some light-tight bellows and a film holder.

- Nevertheless many large format cameras show more freedom when it comes to composition and focussing: Shift, tilt and swing movements of the lens and the film holder allow to shift and rotate the film out of optical axis of the lens. This opens up possibilities to compensate or strengthen the effects perspective (converging lines in tall or wide structures) and to tilt the plane of focus with respect to the plane of the film.

- While digital photography these days sometimes feels a bit like fast food, as it is so easy to just click away so many images per minutes, for each image in analogue large format photography you are forced to take your time, slow down, think more.

The last bit of inspiration needed was incrementally built up by the presence of some old 19th century wooden field camera in my living room (see image above). I got this camera on an auction just for its historic value first. But soon I was inspired by the idea how much fun it would be to reactivate this piece of history and try if I could produce some decent images with it. Unfortunately the bellows have some light leaks and so do the wooden film holders. So the alternative plan was then to get some working specimen of a large format camera from the subsequent century.

Deciding for a camera – The Tachihara 45F:

One prerequisite the camera should fulfill was quickly defined: it should be lightweight enough to be carried on backpacking tours. This would rule out many rather heavy cameras made from metal, such as a Linhof Technika or most monorail studio cameras. Also this would rule out formats larger than 4×5 inches (or the slightly smaller metric equivalent of 9×12 cm), as most 5×7 or 8×10 cameras are very bulky and a pain to lug around without a mule or a car.

After weeks of thinking and research I narrowed my selection of cameras down to this list:

- The Toho Shimo FC-45X monorail camera. One of the very few really lightweight monorail cameras below 2kg

- The Shen-Hao HZX-45IIA wooden field camera

- The Chamonix 045-n2 (or a second hand 045-n1), very lightweight (below 1.5kg) made from wood, metal and carbon fibre

- The Wista Field DX 4×5 or similar

- The Tachihara 4×5 wooden field camera made from cherry wood

I was really keen on the Toho, as a monorail allows usually for the most flexibility in camera movements. However, I soon found out that the Toho went out of production some time ago, and it is close to impossible to get a second hand one on short notice.

I was really keen on the Toho, as a monorail allows usually for the most flexibility in camera movements. However, I soon found out that the Toho went out of production some time ago, and it is close to impossible to get a second hand one on short notice.

The Chamonix would probably have been the most sensible choice as it is the cheapest and lightest of all cameras listed, and the most versatile of the field cameras. However it lacks the really classic appearance of an all wood and metal field camera.

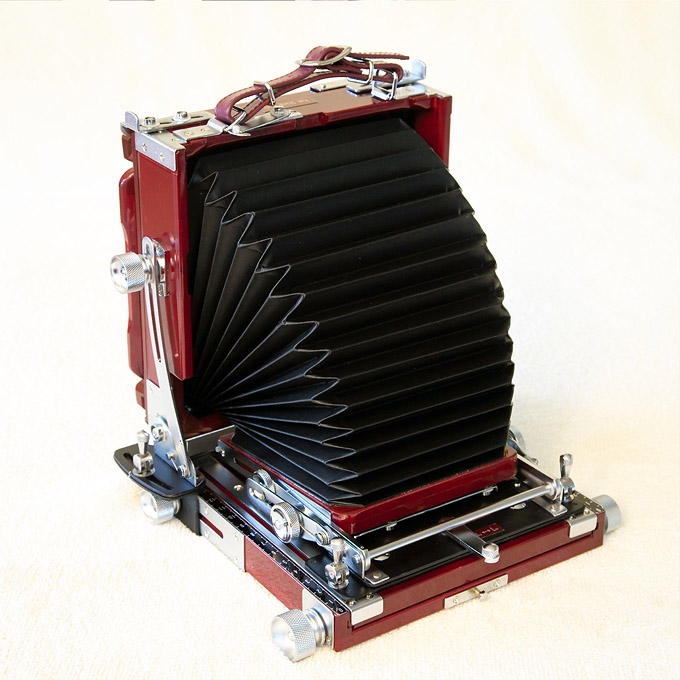

In the end I decided for the Tachihara, as it appears as a real beauty, it is reasonably lightweight (slightly heavier than the 1.5kg stated in the specs though) and it is one of the cheaper cameras but still well built.

I soon found out however, that the Tachihara 45 is not that easy to get in Europe. The used ones you find on ebay or elsewhere are very often in a very bad state or are sold on different continents.

So it took some time, but after some research and hunting I found a dealer in Germany (RK-Photo-Solutions) who had some specimens in stock. A couple of days later – on May 8 2012 – I finally could un-box my Tachihara 45F from 2008!

Below you can see first images of the camera still folded, in the process of unfolding, and fully set up with a lens board but without a lens.

- first of all of course a lens with a shutter

- a wire release

- a sturdy tripod (OK, I have got some tripods to choose from, so not the biggest issue for me right now)

- a light meter (or another camera with a built-in light meter)

- a focussing loupe

- a dark cloth for focussing

- 4×5 sheet film holders

- sheet film

And for the subsequent process of developing:

- all the black and white chemistry and storage containers

- a development tank with 4×5 sheet film holders or as an alternative just some lab trays

- a thermometer

- a stop watch

- oh yes, and a dark room or a light tight bag

At this point I do not plan to do any enlarging by myself. Hence I will not need an enlarger. Instead the plan is to scan the negatives with an Epson V700 flatbed scanner.